No products in the cart.

Inside Balochistan With Willem Marx

Signed copies of Balochistan at a Crossroads, by Willem Marx and Marc Wattrelot, are available directly from the authors via Paypal. You can get plain old unsigned ones via Amazon in the U.S.

“I was supposed to fly to Afghanistan today but my body armor didn’t arrive in time,” was something Willem Marx said to me one of the first times we met. He says things like this on a not infrequent basis. Marx currently works at Bloomberg TV and has reported from the Democratic Republic of Congo, Uzbekistan, the Arctic Circle, and other less trodden parts of the world.

In 2009, he spent time in Pakistan, where he met French photographer Marc Wattrelot. “Balochistan at a Crossroads” is the result of a collaboration between the pair, an unusual coffee table book that focuses on a province in the country whose people are locked in a slow, long-simmering fight for freedom. “It’s a travelogue with some history and reportage,” said Marx, who is donating the publisher’s check to Unicef in the region to help with the efforts to eradicate Polio. “Hopefully, it will give you a sense of a place that realistically, very few of the readers will ever get to visit in the near future.” Body armor optional. We had some questions for him.

Where the heck is this place?

It’s an area that’s divided up between Pakistan and Iran. You have a province in Pakistan called Balochistan and you have a province in Iran called Sistan-va-Baluchestan. The people from the region are called the Baloch, hence the name of the area. They are a bit like the Kurds in the sense that they were carved up by imperial powers. Consequently, they’ve never really been able to establish their own national identity. If you asked the Baloch in Pakistan, they will say they were an independent state before the British arrived, the British recognized their sovereignty, and then after partition they were tricked by the Pakistanis into becoming part of Pakistan.

So the British are the good guys?

I wouldn’t say that. I would say that in this mythical view that many people have, the Baluch got screwed by Muhammad Ali Jinnah, the founder of Pakistan.

How did you end up there?

I lived in Karachi as a kid, which is just outside the province of Balochistan, but I had never really paid any attention to this name I had seen a bunch of times — until 2005. There was a tribal conflict that was flaring up there. I had just graduated college and was in Baghdad. I read this fascinating BBC News story online about how these people were fighting against the Pakistani army with very little in terms of support and very little in terms of artillery.

CIA map of “major ethnic groups” of Pakistan from 1980.

Does everyone in Pakistan know about this conflict?

It’s like the hidden secret. I cannot get a single person to sell this book. It’s quite bizarre. It’s not because the booksellers don’t want to sell it. They are worried that they will have their premises investigated. No wholesaler will import it. It’s really extraordinary. It’s a secret conflict that’s been going on since the 1940s, the latest iteration since 2005. That’s eight years of low-intensity conflict, but you hear very little about it. Maybe there’s something in the Pakistani press, but it’s very difficult as a journalist to get to the region.

I had gone there as a TV journalist and shot some stories there, but I had so much material that wasn’t used in the packages I put together. Marc had hundreds of photographs, and we thought we should do something because it’s so hard to get there.

Do you have any sense of whether they can break away?

They’d love to but I don’t think they are sufficiently well organized and funded. Their template is Bangladesh. At the end of British rule of the subcontinent, Pakistan became two separate nations. Pakistan was split into two very distinct geographical areas, into east and west. East Pakistan was dominated by ethnic Bengalis who won freedom in the early 1970s. That became the nation of Bangladesh. A lot of Baloch will say we want the same kind of thing. But Pakistan is very sensitive of this because it was very humiliating internationally when it lost a large part of its country and population. They were different and so separated. The Baloch are ethnically different to the Punjabis, the Pathans, and the Sindhis. The nationalist Baloch are very hostile to the Punjabis, who have tended to be the elite since partition, but they do have a big contiguous border, so it would be a little more complicated deciding how to demarcate things. I think that unless they get international support, it’s not going to happen anytime soon.

Did you feel in danger when you were traveling there?

It’s a pretty wild place. There’s a lot of banditry. Being a foreigner makes you a bit of a target. The biggest problem is the Pakistani military. Civilian rule doesn’t count for a great deal outside of the provincial capital, Quetta. The soldiers and the intelligence officers tend to be in charge when it comes to security.

Conversely, when I spent time with the militants who are fighting against them, I always felt that they looked after me incredibly well. They obviously wanted the publicity, so it was in their interest to make sure that I was looked after and safe. But it really felt like going back in time. You have these mountain camps where the rebels live in these very austere environments. It’s incredibly hot during the summer and incredibly cold during the winter. They have a degree of local support so they were able to access food and fuel supplies in the villages. There were entire areas that I traveled to in the province that were under their control. The military had pulled back and left entire valley and mountainous areas up to the rebel.

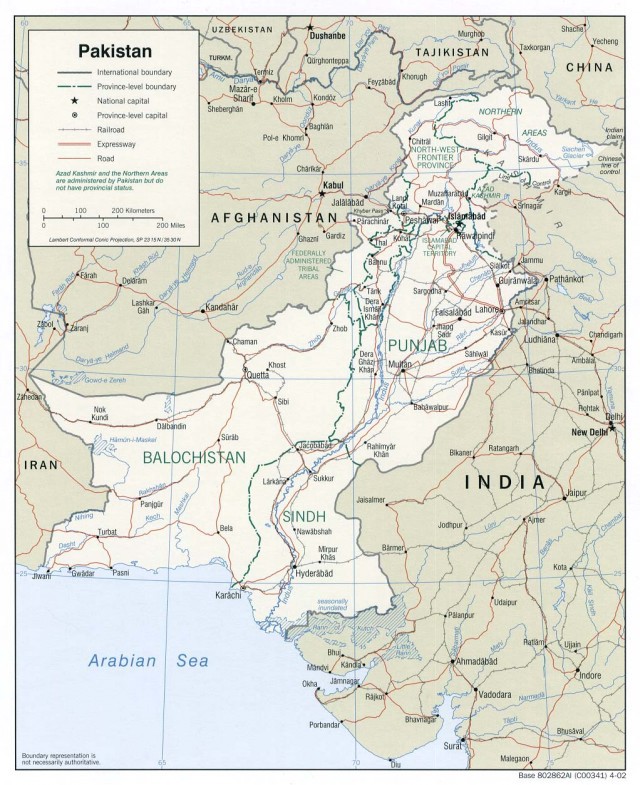

CIA political map of Pakistan from 2002.

What’s the most scared you were?

I went to meet an Iranian Baloch leader on the Pakistani border. The Baloch in Iran are a Sunni population in a majority Shite country, so they are treated both as an ethnic and a religious minority. If you ask the Iranian Baloch, they will say they are trampled upon repeatedly and they are treated as second-class citizens in their own province. I went to visit this militant who the Iranians considered their most wanted terrorist at the time and repeatedly claimed that he was being funded by the Americans, specifically the CIA. He was a very charming, engaging young guy. We were both around 24 or 25.

Going to meet him was really, really scary. I wasn’t allowed to bring my own translator. I wasn’t allowed to bring the guy who had been driving me around the province. I had to take on faith that these guys weren’t going to do any harm. Their ideology leaned pretty heavily Islamist. The Iranians said they were like al-Qaeda. There were certainly videos of them beheading captives like the Iranian Revolutionary Guard and the Iranian border police. I had to get in a car with a bunch of these guys and hope they weren’t going to do any harm.

Spending time with them on the Iranian boarder was really scary. They were constantly being hunted by the Iranian authorities. It was unclear to me whether I was in Iran or Pakistan at the time. The idea of being in Iran, illegally, without a visa, as a journalist, with a bunch of people who they considered terrorists was pretty unnerving. I tried to limit my time spent with them.

There’s been a lot of talk about the difficulty of freelancing as a foreign correspondent. You were doing this piece for Dan Rather Reports, but it was your first story for them and you weren’t on staff. That’s not a whole lot of security.

In hindsight, I probably wouldn’t pursue this story without better guarantees. Subsequently, having worked at places like CBS that have a great deal more resources and support and training…. Essentially, I had no idea what I was doing. I knew how to film. I knew how to put a story together. But if things had gone wrong, it was me in the middle of nowhere on a satellite phone calling people in New York who themselves had no idea where I was. Getting into a car with a bunch of young, Iranian Baloch militants and saying goodbye to the driver and translator who were the only two people I knew within 1,000 miles was a pretty stupid thing to do. But it ended up making me into someone who the TV show in particular wanted to keep around. I worked for them for several years. But in hindsight — I don’t want to say it was a stupid thing to do, but certainly a risky thing to do.

I’ve thought about that a lot in the subsequent years. It’s one of the difficult things in this line of work. To get attention as a young person, you have to almost go and do stories that other people don’t want to do and put yourself in harm’s way. Now, at age 31, I would a) ask for a lot more money and b) want to know that there were better safeguards. For me, this was a fascinating story and an incredible place to be able to visit and the opportunity was the one that I seized but in hindsight, very risky.

How did you prepare for the trip to Balochistan? You’re basically just parachuting into a place and trying to figure it out quickly.

Well, I was never going to fit in even though I did grow a pathetic attempt at a beard. That said, I spent what was essentially a month reading everything I could get my hands on and speaking to as many people as possible. If every story I ever did could be one in which I could do that, I would be very happy. I was very well prepared in terms of my background knowledge. I didn’t know what to expect physically when I arrived there but I knew what was going on.

That’s one of the amazing things about our generation’s access to information. You can turn up in a place completely alien to you, but because of the Internet you can have read hundreds of thousands of local news accounts that give you a sense of what’s going on there. If you went back to a previous generation of foreign correspondents, that wasn’t possible. You could make as many phone calls as you wanted but it wouldn’t give you quite as much depth and context as you now have access to.

It’s like we’ve traded individual institutional knowledge for a collective knowledge or something like that.

Yeah, and since then, it’s changed even more. Using things like Twitter and Facebook, I could have set up half my interviews in advance. Instead, I relied a network of underground activists. I managed to get permission to travel around Balochistan by explaining that I wanted to do economic reporting in this very economically marginalized province. At the time, President Zardari was talking a big game about what he was able to do about economic improvement in the Balochistan province. Somewhere, I think that struck a chord and they thought it was a good idea. I had the name Dan Rather behind me, and Pakistani press officials knew who he was. So that helped. I don’t think they suspected I’d be doing stories about the Baloch Liberation Army. That might be more difficult now.

Please login to join discussion

easyComment URL is not set. Please set it in Theme Options > Post Page > Post: Comments